Editor’s Note: As a companion piece to my ongoing ramble through the delights of thrilling all’italiana, Giallo-a-Go-Go, I’ve invited poster expert and chum Sim Branaghan to contribute a Guest Post detailing the British Experience of this hot-blooded genre, more specifically through the poster images used by UK quad illustrators and designers. (Anyone who hasn’t already done so is urged to check out Sim’s definitive history of the UK Quad Crown poster, British Film Posters: An Illustrated History [BFI, 2006], available here.)

The Giallo in Britain: 1965-1983

The Giallo in Britain: 1965-1983

Let’s start with the basics—just what is a ‘giallo’? The term is a popular nickname for a specific genre of Italian murder-mystery crime-thriller that flourished for about twenty years, c.1963-83. Like their contemporary cousin the Spaghetti Western, the gialli also achieved a notable overseas success despite (or perhaps because of) their uniquely stylised national identity. With their controversial mix of heavily-fetishised sex and violence they have since gone on to enjoy much enthusiastic attention from such well-known UK film buffs as the Metropolitan Police’s Obscene Publications Squad.

Warner-Pathe’s quad for Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much/The Evil Eye (1963), with art crudely adapted from the US campaign by AIP (pictured left).

The first officially-recognised giallo is Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963), while the last to achieve a decent international release was Dario Argento’s Tenebrae (1982). In between these two landmarks (depending upon how tightly one applies the qualifying criteria) is a sequence of about 140 steadily more lurid melodramas.  This essay however is concerned with the much smaller number that actually made it into British cinemas. How did a repressed, uptight nation of censorious prudes cope with the wildly baroque sensationalism of the giallo? (One answer, as noted, was to decide that many—at least on Home Video—were probably illegal). Another approach, as we shall shortly discover, was to conversely try and pretend they were far more dull and conventional than was actually the case. This idea can be explored by considering two linked elements: their UK re-titlings and associated publicity campaigns, specifically posters.

This essay however is concerned with the much smaller number that actually made it into British cinemas. How did a repressed, uptight nation of censorious prudes cope with the wildly baroque sensationalism of the giallo? (One answer, as noted, was to decide that many—at least on Home Video—were probably illegal). Another approach, as we shall shortly discover, was to conversely try and pretend they were far more dull and conventional than was actually the case. This idea can be explored by considering two linked elements: their UK re-titlings and associated publicity campaigns, specifically posters.

Forty gialli were released in Britain 1965-83, the majority during the boom years of 1970-73. One important factor undoubtedly influencing their appearance here was the revision of the BBFC’s Certification system in July 1970, which (amongst other things) raised the age-bar of the Adults Only ‘X’ film from 16 to 18, allowing greater flexibility in what could be passed for exhibition. The entirely predictable result of this initiative was a headlong rush to permissiveness in which the giallo—which shamelessly exploited these new freedoms to the full—played a key part.

The following list is arranged chronologically by date of British release, and includes both original Italian title (where this differed from the UK version) and individual distributor.

The Films

Original Italian titles are italicised (followed by a literal English translation), with UK re-titles underlined. If identical only the latter are given.Where the film is generally better-known by a different English title, that title is supplied [in brackets.]

1) La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much) (Bava 1963) ‘The Evil Eye’ April 1965 Warner-Pathe

1) La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much) (Bava 1963) ‘The Evil Eye’ April 1965 Warner-Pathe

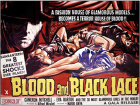

2) Sei donne per l’assassino (Six Women For the Killer) (Bava 1965) ‘Blood and Black Lace’ Feb 1966 Gala

2) Sei donne per l’assassino (Six Women For the Killer) (Bava 1965) ‘Blood and Black Lace’ Feb 1966 Gala

3) ‘Libido’ (Gastaldi 1965) April 1967 New Realm

4) Il dolce corpo di Deborah (Guerrieri 1968) ‘The Sweet Body of Deborah’ Nov 1968 Eagle

4) Il dolce corpo di Deborah (Guerrieri 1968) ‘The Sweet Body of Deborah’ Nov 1968 Eagle

5) La lama nel corpo (The Blade in the Body) (Scardamaglia 1966) ‘The Murder Clinic’ May 1969 Border

5) La lama nel corpo (The Blade in the Body) (Scardamaglia 1966) ‘The Murder Clinic’ May 1969 Border

6) La morte ha fatto l’uovo (Death Laid an Egg) (Questi 1968) ‘A Curious Way to Love’ May 1969 Butchers

7) La morte non ha sesso (Death Has No Sex) (Dallamano 1968) ‘A Black Veil for Lisa’ Nov 1969 Commonwealth

7) La morte non ha sesso (Death Has No Sex) (Dallamano 1968) ‘A Black Veil for Lisa’ Nov 1969 Commonwealth

8) Orgasmo (Lenzi 1968) ‘Paranoia’ Jan 1970 Commonwealth

8) Orgasmo (Lenzi 1968) ‘Paranoia’ Jan 1970 Commonwealth

9) L’uccello dale piume di cristallo (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage) (Argento 1970) ‘The Gallery Murders’ Nov 1970 Eagle

9) L’uccello dale piume di cristallo (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage) (Argento 1970) ‘The Gallery Murders’ Nov 1970 Eagle

10) Una sull’altra (Fulci 1969) ‘One On Top of the Other’ March 1971 Border

10) Una sull’altra (Fulci 1969) ‘One On Top of the Other’ March 1971 Border

11) La morte risale a ieri sera (Tessari 1970) ‘Death Occurred Last Night’ June 1971 Eagle

11) La morte risale a ieri sera (Tessari 1970) ‘Death Occurred Last Night’ June 1971 Eagle

12) Il gatto a nove code (Argento 1971) ‘The Cat O’ Nine Tails’ June 1971 National General

12) Il gatto a nove code (Argento 1971) ‘The Cat O’ Nine Tails’ June 1971 National General

13) Nude..si muore (Naked—You Die) (Margheriti 1968) ‘The Young the Evil and the Savage’ July 1971 London Screen

13) Nude..si muore (Naked—You Die) (Margheriti 1968) ‘The Young the Evil and the Savage’ July 1971 London Screen

14) Il mostro di Venezia (The Monster of Venice) (Tavella 1964) ‘The Embalmer’ Feb 1972 D.U.K.

14) Il mostro di Venezia (The Monster of Venice) (Tavella 1964) ‘The Embalmer’ Feb 1972 D.U.K.

15) Le foto proibite di una signora per bene (Ercoli 1970) ‘Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion’ June 1972 Butchers

15) Le foto proibite di una signora per bene (Ercoli 1970) ‘Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion’ June 1972 Butchers

16) 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto (Bava 1970) ‘Five Dolls for an August Moon’ Aug 1972 EJ Fancey

16) 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto (Bava 1970) ‘Five Dolls for an August Moon’ Aug 1972 EJ Fancey

17) Concerto per pistol solista (Concerto for Solo Pistol) (Lupo 1970) ‘The Weekend Murders’ Sept 1972 MGM

17) Concerto per pistol solista (Concerto for Solo Pistol) (Lupo 1970) ‘The Weekend Murders’ Sept 1972 MGM

18) La tarantola dal ventre nero (Cavara 1971) ‘Black Belly of the Tarantula’ Dec 1972 MGM

19) La notte che Evelyn usci’ dalla tomba (The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave) (Miraglia 1971) ‘The Night She Rose From the Tomb’ Dec 1972 Miracle

19) La notte che Evelyn usci’ dalla tomba (The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave) (Miraglia 1971) ‘The Night She Rose From the Tomb’ Dec 1972 Miracle

20) La bestia uccide a sangue freddo (The Beast Kills in Cold Blood) (Di Leo 1971) ‘Cold-Blooded Beast’ Jan 1973 Miracle [A.k.a. Slaughter Hotel]

21) Il rosso segno della follia (The Red Sign of Madness) (Bava 1970) ‘Blood Brides’ Feb 1973 Tigon [A.k.a. Hatchet for the Honeymoon]

21) Il rosso segno della follia (The Red Sign of Madness) (Bava 1970) ‘Blood Brides’ Feb 1973 Tigon [A.k.a. Hatchet for the Honeymoon]

22) Alla ricerca del piacere (In the Pursuit of Pleasure) (Amadio 1972) ‘Hot Bed of Sex’ Feb 1973 English Film Company [A.k.a. Amuck!]

22) Alla ricerca del piacere (In the Pursuit of Pleasure) (Amadio 1972) ‘Hot Bed of Sex’ Feb 1973 English Film Company [A.k.a. Amuck!]

23) 4 mosche di velluto grigio (Argento 1971) ‘Four Flies on Grey Velvet’ March 1973 Paramount (CIC)

23) 4 mosche di velluto grigio (Argento 1971) ‘Four Flies on Grey Velvet’ March 1973 Paramount (CIC)

24) Perche quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (Why These Strange Drops of Blood on Jennifer’s Body?) (Carnimeo 1972) ‘Erotic Blue’ April 1973 Border [A.k.a. Case of the Bloody Iris]

24) Perche quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (Why These Strange Drops of Blood on Jennifer’s Body?) (Carnimeo 1972) ‘Erotic Blue’ April 1973 Border [A.k.a. Case of the Bloody Iris]

25) I due volti della paura (Demichelli 1972) ‘The Two Faces of Fear’ April 1973 Border

26) Paranoia (Lenzi 1969) ‘A Quiet Place to Kill’ May 1973 Eagle

26) Paranoia (Lenzi 1969) ‘A Quiet Place to Kill’ May 1973 Eagle

27) Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (Fulci 1971) ‘A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin’ July 1973 Gala

28) Il tuo vizio è una stanza chiusa e solo io ne ho la chiave (Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key) (Martino 1972) ‘Excite Me’ July 1973 Border

29) Giornata nera per l’ariete (Black Day For Aries) (Bazzoni 1971) ‘Evil Fingers’ Nov 1973 Target [A.k.a. The Fifth Cord]

30) L’occhio nel labirinto (The Eye in the Labyrinth) (Caiano 1971) ‘Blood’ Aug 1974 Border

31) I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale (The Bodies Show Signs of Carnal Violence) (Martino 1973) ‘Torso’ June 1975 Variety

32) L’assassino è al telefono (de Martino 1972) ‘The Killer is on the Phone’ Dec 1975 Cathay

32) L’assassino è al telefono (de Martino 1972) ‘The Killer is on the Phone’ Dec 1975 Cathay

33) Sette scialli di seta gialla (Seven Shawls of Yellow Silk) (Pastore 1972) ‘The Crimes of the Black Cat’ April 1976 Border

33) Sette scialli di seta gialla (Seven Shawls of Yellow Silk) (Pastore 1972) ‘The Crimes of the Black Cat’ April 1976 Border

34) ‘Suspiria’ (Argento 1977) Oct 1977 EMI

34) ‘Suspiria’ (Argento 1977) Oct 1977 EMI

35) Passi di danza su una lama di rasoio (Dance Steps on a Razor Blade) (Pradeux 1973) ‘Maniac At Large’ June 1978 Border [A.k.a. Death Carries a Cane] [Image courtesy of Paul Waines.]

36) Enigma rosso (Red Enigma) (Negrin 1978) ‘Red Rings of Fear’ March 1979 Bordeaux

36) Enigma rosso (Red Enigma) (Negrin 1978) ‘Red Rings of Fear’ March 1979 Bordeaux

37) Nude per l’assassino (Nude Women for the Killer) (Bianchi 1975) ‘Strip Nude For Your Killer’ March 1980 Golden Era

38) Reazione a catena (Chain Reaction) (Bava 1971) ‘Bloodbath’ May 1980 New Realm [A.k.a. A Bay of Blood]

38) Reazione a catena (Chain Reaction) (Bava 1971) ‘Bloodbath’ May 1980 New Realm [A.k.a. A Bay of Blood]

39) ‘Inferno’ (Argento 1980) Oct 1980 Fox

39) ‘Inferno’ (Argento 1980) Oct 1980 Fox

40) Tenebre (Argento 1982) ‘Tenebrae’ May 1983 Anglo-American

40) Tenebre (Argento 1982) ‘Tenebrae’ May 1983 Anglo-American

MGM’s double-bill quad for The Black Belly of the Tarantula/The Weekend Murders, an unexciting revamp of their US campaign (pictured left).

The UK distribution of overseas exploitation like the gialli is an interesting topic in itself. Very few of the major studios handled such cheap imports (having enough product of their own to shift), and in any case the gialli (unlike, say, kung fu just a year or two later) never broke through as a distinctive pop-cultural fad.  Warner-Pathe released The Evil Eye as part of their long-standing relationship with AIP in the States (who had successfully played it in the drive-ins). MGM had similarly promoted Black Belly of the Tarantula and The Weekend Murders as a double-bill in the US, and dutifully repeated the package over here. The remainder of the Majors’ involvement was limited to boy-wonder Dario Argento: Paramount had released Four Flies on Grey Velvet in America and did the same here in 1973, EMI gave Suspiria a big push in 1977, and Fox reluctantly granted Inferno a much smaller (London only) showing at the tail-end of the cycle in 1980.

Warner-Pathe released The Evil Eye as part of their long-standing relationship with AIP in the States (who had successfully played it in the drive-ins). MGM had similarly promoted Black Belly of the Tarantula and The Weekend Murders as a double-bill in the US, and dutifully repeated the package over here. The remainder of the Majors’ involvement was limited to boy-wonder Dario Argento: Paramount had released Four Flies on Grey Velvet in America and did the same here in 1973, EMI gave Suspiria a big push in 1977, and Fox reluctantly granted Inferno a much smaller (London only) showing at the tail-end of the cycle in 1980.

Paramount’s quad for Dario Argento’s Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), repurposing elements of their US campaign (pictured right).

Apart from these six, every other film on the list was independently released. A dozen were handled by one linked group of family companies alone: Edwin John Fancey (together with his common-law wife Olive Negus and eldest daughter Adrienne) ran New Realm, Border, D.U.K. Films, EJ Fancey Prods, and several others over a period of almost fifty years from various addresses in Wardour Street W1. EJ (1902-1980) is now generally recognised as the most significant force in lowbrow UK exploitation prior to the arrival of Tony Tenser in 1960, and was by all accounts a Colourful Character.

Border’s 1969 release of The Murder Clinic (1966), with its helpfully succinct tagline: “Blood…Horror.”

He entered the business just before the War, and spent the majority of 1945 behind bars after stabbing his accountant in the leg during a heated altercation over his business methods. We can only speculate as to how EJ went about preparing for the trial, but by the time the case came to court the victim had changed his story so dramatically he was regarded by the prosecution as a hostile witness. EJ soon bounced back, moving into an imposing Elizabethan manor house in Worthing with his wife Beatrice (while installing Olive in the adjacent gatehouse), running several racehorses at Epsom, and generally living the life of a Cockney mogul. The accountant (whose sciatic nerve had been practically severed in the attack) subsequently lost the leg.

Sergio Pastore’s 1972 giallo Crimes of the Black Cat finally saw a UK release via Border in 1976, paired with The Horrible Sexy Vampire (1970). This quad layout could be the work of designer Mike Wheeler, who worked for E.J.Fancey almost exclusively throughout the 1970s. The design is a crude reworking of elements from the Italian locandina (pictured right).

Border (who were active between 1957-78, and released eight gialli in the latter half of the period) was one of Olive’s companies, and had initially specialised in children’s films. It is unclear whether the proprietress had any personal enthusiasm for the genre, but some of her re-titlings are certainly amongst the most memorable (for all the wrong reasons).

Here we have a double-winner: the worst retitling (Death Carries a Cane wasn’t great, but Maniac at Large?) married with the worst quad design. As can be seen from the Italian art (right), Border’s UK campaign was another lumpen repurposing of country-of-origin poster art (by Mario Piovano). [Image courtesy of Paul Waines.]

Emilio P. Miraglia’s The Night Evelyn Came out of the Grave (1972) was paired with Fernando di Leo’s ludicrous Cold-Blooded Beast (1971) for its 1973 release by Miracle.

Other key companies handling gialli in Britain were Miracle (active 1953-86), Gala (1958-85), and Eagle (1962-83), all of whom specialised in importing what were then known as Continental Films, generally featuring saleable ‘spicy’ content. (Sexploitation producer Stanley Longlater reminisced “I remember in 1956 I travelled over to the other side of London to see a subtitled French film that was reputed to have a nipple showing”). The most upmarket of the trio was probably Gala, whose amiable boss Kenneth Rive (1918-2002) is the only character in this story to have been eulogised in all the UK broadsheets, where he was hailed as the man who introduced Truffaut and the Nouvelle Vague to British audiences. Mind you, he also introduced them to a lot of sleazy rubbish in order to pay the rent, and any cineastes indignantly objecting to this assessment have clearly never sat through A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin. Still, at least he never stabbed his accountant in the leg.

Miracle were somewhat more downmarket – as their original publicity head Tony Tenser (1920-2007) liked to chortle “If it’s a good film then it’s a Miracle!” Boss Michael Myers (1928-1998) later helped launch John Carpenter’s career by snapping up the UK rights to Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), and Carpenter slyly repaid the debt by naming the unstoppable killer in Halloween after him in tribute. Unlike Gala, Miracle rarely ventured into Art, preferring to chiefly stick with straight exploitation. The practical dividing line in this context is really the availability of an English-dubbed soundtrack – neither Myers nor Tenser (subsequently to head Tigon) were naïve enough to expect their target audience to read a load of subtitles.

Tigon released Mario Bava’s Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1969) as Blood Brides in 1973, supporting The Creeping Flesh.

Butcher’s 1969 UK release of Giulio Questi’s eccentric Death Laid an Egg (1968) sold the film as up-market erotica, under the new title A Curious Way To Love.

Eagle’s quad for City of the Living Dead (1981); art by Enzo Sciotti. Pictured left, the Italian art for The New York Ripper, denied a UK release by the BBFC in 1984.

Eagle, run by Barry Jacobs (1933-1998 and another wheeler-dealer of the old school) handled an eclectic mix of high and lowbrow fare. They started out very worthily importing filmed operas like La Traviata (1967), but by the 1980s were reduced to pushing Lucio Fulci’s later gothic  horrors like City of the Living Dead (1981)—by that point practically the only Italian films still getting a UK release. The full-stop for Eagle (and ultra-violent foreign exploitation in general) came in February 1984 when Jacobs rather optimistically submitted Fulci’s New York Ripper—perhaps the most notorious giallo of them all—to the BBFC for classification. James Ferman was so appalled he not only refused it a Certificate outright, but also (according to legend) instructed a Customs official to personally escort the offending print back out of the country.

horrors like City of the Living Dead (1981)—by that point practically the only Italian films still getting a UK release. The full-stop for Eagle (and ultra-violent foreign exploitation in general) came in February 1984 when Jacobs rather optimistically submitted Fulci’s New York Ripper—perhaps the most notorious giallo of them all—to the BBFC for classification. James Ferman was so appalled he not only refused it a Certificate outright, but also (according to legend) instructed a Customs official to personally escort the offending print back out of the country.

[Bava’s Reazione a catena (1971) suffered a similar Rejection when first submitted by New Realm under its alternate title Bay of Blood in April 1972. The company doggedly tried again (as Bloodbath) eight years later, and the BBFC this time reluctantly awarded it an ‘X’ after removing almost five minutes of footage. As an aside, Luciano Ercoli’s 1971 giallo Death Stalks on High Heels was intriguingly also submitted and passed ‘X’ in May 1972, but seems never to have been released.]

Dario Argento’s global hit The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1970) was retitled The Gallery Murders by UK distributor Eagle, and given a campaign that might charitably be described as weak.

Still, Bird fared better than Duccio Tessari’s Death Occurred Last Night, whose quad practically screams “don’t bother; after all, we didn’t”.

And that’s how it’s done: Franco Picchioni’s superb art for the Italian due-fogli poster of Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1970).

Another interesting element to consider in terms of the gialli’s UK distribution is each individual film in the sequence’s co-feature. At this point, double-bills were standard practice in British exhibition, though these were not always advertised as such if the support was considered too minor to be worth promoting. Referring back to our original numbered list, the following 36 films were paired with their numerical counterpart (17-18 and 19-20 are omitted, as they were double-billed with each other). A two-letter code indicates country of origin, while titles preceded with a ‘?’ are currently unconfirmed most likely candidates.

Cathay’s 1975 quad for The Killer is on the Phone (1972), paired with Aussie kung-fu epic The Man From Hong Kong (1973).

1) Comedy of Terrors [US] 2) Four Kinds of Love [IT] 3) Trapped By Fear [FR] 4) Rage [US] 5) Devil’s Man [IT] 6) Some May Live [UK] 7) That Cold Day in the Park [US] 8) 99 Women [SP] 9) Groupie Girl [UK] 10) Games That Lovers Play [UK] 11) Love Box [UK] 12) ? Todd Killings [US] 13) Eyes of Hell [CA] 14) Diabolical Dr Z [SP] 15) Street Of Sin [GM] 16) Naked and Violent [IT] 21) Creeping Flesh [UK] 22) Erotic Love Games [FR] 23) Ulzana’s Raid [US] 24) I am Sexy [FR] 25) ? Night of the Devils [IT] 26) Sex and the Other Woman [UK] 27) ? Danish Bed and Board [DK] 28) Naughty Nun [IT] 29) Wonder Women [US] 30) ? The Lovemakers [IT] 31) Flesh Gordon [US] 32) Man From Hong Kong [AU] 33) Horrible Sexy Vampire [SP] 34) Genesis: A Band in Concert [UK short] 35) Love—Vampire Style [GM] 36) Trip to Kill [US] 37) ? Sister Emanuelle [IT] 38) Human Experiments [US] 39) ? Steppin’ Out [UK short] 40) ? Bird With the Crystal Plumage [IT]

So much for the distributors themselves. Having briefly sketched in a few of the characters responsible for bringing the gialli to Britain (and what they did with them), we can now turn our attention to how the films were actually sold over here. The first important element to consider is their titles.

Border’s quad for the lively Edwige Fenech giallo Case of the Bloody Iris, imaginatively-retitled Erotic Blue for the raincoat brigade (1972). The original Italian artwork is pictured left.

As any fan will tell you, one of the most distinctive features of the gialli were their impossibly ornate and convoluted original titles. These often utilised recurring stylistic tropes focussing on animals (unusual), colours (vivid), and numbers (meaningful). Failing that,  they simply posed outrageous questions (“Why these strange drops of blood on Jennifer’s body?”) or offered even more outrageous assertions (“Your vice is a locked room and only I have the key”). Some were so callously blunt they seemed wilfully provocative (“The bodies show signs of carnal violence”). English-speaking audiences, it was clearly felt, would react with confused bafflement to anything so quirky and needed to be spoon-fed a reassuringly bland mix of clichés instead.

they simply posed outrageous questions (“Why these strange drops of blood on Jennifer’s body?”) or offered even more outrageous assertions (“Your vice is a locked room and only I have the key”). Some were so callously blunt they seemed wilfully provocative (“The bodies show signs of carnal violence”). English-speaking audiences, it was clearly felt, would react with confused bafflement to anything so quirky and needed to be spoon-fed a reassuringly bland mix of clichés instead.

Of the forty UK-released gialli, 22 were re-titled and 18 retained their original Italian name (or a close approximation thereof). No consistent approach is discernible and it seems simply to have been down to the whims of the individual distributor. Sometimes the new titles were admittedly superior (or at least more commercial)—The Evil Eye is much punchier than the rather generic The Girl Who Knew Too Much, and Blood and Black Lace is more salaciously inspired than the dull Six Women For the Killer. But these are the minority. All too often lowest-common-denominator is in operation: The Gallery Murders must be the single most boring title ever devised for a thriller. Others are blatantly opportunistic—The Young the Evil and the Savage is a hopelessly crude attempt to invoke The Good the Bad and the Ugly.

Silvio Amadio’s Alla ricerca del piacere (1972) was retitled Hot Bed of Sex by the English Film Company in 1973.

Some changes could simply be pragmatic: Hot Bed of Sex is undeniably crasser than the elegant In the Pursuit of Pleasure, but—given the amount of irrelevant slow-motion romping the film showcases—is actually a fair description of the goods. Re-titling might also be genuinely unavoidable—Orgasmo was (unsurprisingly) released internationally as Paranoia, and director Umberto Lenzi clearly liked the new name so much he immediately re-used it on his next film, which thus also had to be changed overseas. But nothing can excuse some of the clod-hopping nonsense foisted on other entries, which Border in particular seemed hell-bent on reducing to inanity: Erotic Blue, Excite Me, Blood, Maniac At Large, Evil Fingers, Bloodbath….. did ANYONE seriously think these were good titles?

Umberto Lenzi’s Orgasmo (1968) was retitled Paranoia for both the US (right) and the UK, the latter release handled by Commonwealth. Note the slightly altered tagline, with “erotic love” (US) amended to “torrid love” (UK).

Closely tied to the issue of new names is that of the new posters promoting them, though here we have to concede some practicalities. Words of course are free—posters are not. The publicity budgets for some of these releases must have been truly tiny, and the distributors would often not have been able to afford the luxury of standard four-colour litho, let alone the services of an illustrator to paint them a bold new design in the first place. The only option in such cash-strapped circumstances was to either print a crude silkscreened version of previously-used art (The Evil Eye) or just throw together a few stills for a slapdash photo-montage (Death Occurred Last Night). The results, as can be seen, were frequently appalling.

This is all the more regrettable when many of the original Italian posters are truly superb – vividly colourful, wildly imaginative designs often deploying striking surrealistic motifs, and painted by a small group of classically-trained artists who were amongst the most distinctive illustrators of their generation. Many of these posters effortlessly capture the MOOD of the darkly stylish films they were promoting. In painful contrast, the British posters frequently tend to have the opposite effect, stolidly reinforcing the impression (already conveyed by the new titles) that what is on offer is cheap rubbish for the terminally undiscerning.

Antonio Margheriti’s Naked…You Die (1968) was misleadingly retitled The Young, The Evil and the Savage for its 1971 release through London Screen, double-billed with Canadian 3D chiller The Mask, a.k.a. Eyes of Hell (1961).

Rodolfo Gasparri’s art for 5 Dolls for an August Moon (1970), also utilised for the UK quad (not pictured).

To be quite fair though, attempting a definitive overview is undermined by the fact that it is next to impossible to assemble a complete set of images. Some of these posters are SO obscure that the present writer (a dedicated collector for 35 years) cannot recall ever seeing arelevant example. At the time of writing there are still about a dozen ‘missing’ images in the sequence, and any readers who can fill one or more of the gaps are encouraged to get in touch. As far as the currently-absent titles go, it can be difficult to know whether the theoretical poster is (i) a single-feature, (ii) a double-bill, or (iii) simply non-existent. Two double-bills that ARE known to exist are Five Dolls for an August Moon (a cheap silkscreen of Rodolfo Gasparri’s original art, second-featured to Naked and Violent), plus Maniac At Large/Love—Vampire Style. [Note: The latter image has recently been supplied by Paul Waines, and can now be admired in all its ghastly two-tone “beauty. See above.]

In other cases it is uncertain whether British posters were even printed at all: for example A Quiet Place to Kill, Evil Fingers and Torso supported Sex and the Other Woman, Wonder Women and Flesh Gordon respectively, but while posters for the three main features are all common, no double-bill versions are known to exist. (This is certainly the case with some of the more obscure Spaghetti Westerns released in the UK as support-features, which had no dedicated publicity produced at all).

Gala’s 1966 quad for Bava’s Blood & Black Lace, illustrated by Fred Payne (and based on original Italian art by Mauro Colizzi, pictured left).

Of the posters actually illustrated, only eight are worthy of brief discussion. Blood and Black Lace is a colourful repainting by Gala’s house-artist Fred Payne of Mauro Colizzi’s original Italian design, slightly more crudely rendered than its inspiration but still very effective. Payne was also responsible for both The  Embalmer and (probably) One On Top of the Other, though the latter is not in his typical style. The Sweet Body of Deborah is almost certainly the work of Jim Tate, and is again a striking re-jig of elements from the Italian campaign, though the large blue portrait of Jean Sorel unmistakeably betrays the influence of Renato Fratini. Suspiria is an imaginative photographic comp (mirroring the films gaudy red/green colour scheme) from the Feref design studio, in all likelihood the work of boss Eddie Paul. For once the tagline—“The most frightening film you’ll ever see!”—is not much of an exaggeration.

Embalmer and (probably) One On Top of the Other, though the latter is not in his typical style. The Sweet Body of Deborah is almost certainly the work of Jim Tate, and is again a striking re-jig of elements from the Italian campaign, though the large blue portrait of Jean Sorel unmistakeably betrays the influence of Renato Fratini. Suspiria is an imaginative photographic comp (mirroring the films gaudy red/green colour scheme) from the Feref design studio, in all likelihood the work of boss Eddie Paul. For once the tagline—“The most frightening film you’ll ever see!”—is not much of an exaggeration.

Eagle’s 1968 quad for Romolo Guerrieri’s The Sweet Body of Deborah, possibly illustrated by Jim Tate.

Border’s 1971 quad for Lucio Fulci’s 1969 giallo One on Top of the Other, possibly the work of illustrator Fred Payne.

The Monster of Venice (1964) was released in the UK as The Embalmer by D.U.K. in 1972 (art: Fred Payne), partnered with Jess Franco’s The Diabolical Dr Z (1966).

Red Rings of Fear was painted by perhaps the most famous British poster-artist of them all, Tom Chantrell. The commission came via Chantrell’s regular agent of the time Alan Wheatley, and thanks to the latter’s job-book we know both how much the artist was paid (£325) and how many copies were printed (750). The latter is just about the lowest possible economic run for a litho poster—the one/two colour silkscreen examples illustrated here would probably have had no more than 300—400 copies produced, and possibly less than that.

Red Rings of Fear was painted by perhaps the most famous British poster-artist of them all, Tom Chantrell. The commission came via Chantrell’s regular agent of the time Alan Wheatley, and thanks to the latter’s job-book we know both how much the artist was paid (£325) and how many copies were printed (750). The latter is just about the lowest possible economic run for a litho poster—the one/two colour silkscreen examples illustrated here would probably have had no more than 300—400 copies produced, and possibly less than that.

Quad art for Fox’s “blink-and-you’ll-miss-it” UK cinema release for Argento’s Inferno (1980); the Italian key art, by Enzo Sciotti, is pictured left.

Most international campaigns for Inferno utilised Enzo Sciotti’s Italian ‘skull-face’ key art, but the British poster instead uniquely opted for a superb panoramic still from the fiery climax, as Mater Tenebrarum’s art-deco palace goes up spectacularly in flames around her—arguably the most dramatically  memorable of all the UK designs. Finally, Tenebrae DID re-use Sciotti’s (notably grim) Italian corpse-art, but featured a restrained British twist courtesy of the Graffiti studio’s Paul Constable. In place of Sciotti’s gruesome trickle of blood, Constable added a scarlet neck-ribbon—the obvious intention was to try and soften the image, but in fact the flirtatious ribbon somehow made the already morbid design seem even MORE necrophilic. A highly suitable finale, one might thus argue, for the entire outrageous cycle.

memorable of all the UK designs. Finally, Tenebrae DID re-use Sciotti’s (notably grim) Italian corpse-art, but featured a restrained British twist courtesy of the Graffiti studio’s Paul Constable. In place of Sciotti’s gruesome trickle of blood, Constable added a scarlet neck-ribbon—the obvious intention was to try and soften the image, but in fact the flirtatious ribbon somehow made the already morbid design seem even MORE necrophilic. A highly suitable finale, one might thus argue, for the entire outrageous cycle.

The Graffiti studio’s tasteful reinterpretation of the Italian key art (pictured right) by Enzo Sciotti, for the 1983 UK cinema release by Anglo-American.

So, having considered how the gialli were sold in Britain, one final question remains—what impact did they have on British culture? On a superficial level, not much: as already argued, they were a distinctively Italian phenomenon, born of a combination of that country’s passionate temperament, obsession with style, and (above all) deeply conflicted Catholic sensibility regarding sex—nowhere is the Madonna/Whore ambivalence towards women more graphically illustrated than in the giallo. For the average British audience, passion, style and overt sexuality were exotic qualities belonging to other people, to be regarded with caution and even distaste. But on a more practical basis, the influence of the giallo on our own increasingly murky exploitation cinema—ever ready to respond to fresh commercial ideas—was immediate and far-reaching. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Argento and co must have felt very flattered indeed.

Picking ten titles at random, all of the following British thrillers are heavily indebted—either thematically, stylistically or both—to the Italians:

The Psychopath (Freddie Francis 1966), Theatre of Death (Sam Gallu 1967), The Haunted House of Horror (Michael Armstrong 1969), Crucible of Terror (Ted Hooker 1971), Assault (Sidney Hayers 1971), Night After Night (Lindsay Shonteff 1971), Madhouse (Jim Clark 1973), Scream and Die (Jose Larraz 1974), Schizo (Pete Walker 1976—along with much of this director’s 70s output), and The Playbirds (William Roe 1978). And these are just the OBVIOUS examples.

Every fan will have their own favourite from this ad-hoc list, but for the present writer the Cornish-set Crucible of Terror is a particular delight. Of course, Rome is the eternally-glamorous essential location for a classic genre entry, but anyone who has enjoyed the diverting spectacle of Mike Raven and Mary Maude chasing each other around St Agnes’s crumbling tin mines will be forced to admit that the giallo had—in however unlikely a fashion—become a truly international phenomenon.

The classic Hokushin video-sleeve for Mario Bava’s ‘Bloodbath’, designed and illustrated by the great Arnaldo Putzu. Released in Feb 1983 and banned as a Video Nasty just a year later in March 1984, this was never officially removed from the DPP’s List and is a lasting testament to the Giallo’s subversive power to provoke censors everywhere.

© Sim Branaghan November 2015